Infertility-Related and Prenatal Depression, Uncovering The Real Struggles

You would deduce that with a bundle of joy on the way, you would feel nothing but—well as the saying goes, joy. But what if you don’t? Or maybe part of you is excited to be expecting, however you have inexplicable sadness. Or perhaps you would love nothing more than to fall pregnant, but are dealing with biological issues, medical interventions, hormone treatments, loss and constant setbacks leading to a distressed state of mind.

We have heard about postpartum depression. However, what about prenatal depression? Or infertility-related depression? With the emphasis on pre, the before-baby blues are not just something in your head. It’s time to put shame and stigma aside to shine a light on what can only be described as a very dark time for sufferers of both these conditions.

Painful path to parenthood: infertility-related depression

Trying to become a mother can be a battle behind closed doors, but staying silent can have detrimental effects on one’s mental disposition. For Natalie Kalfus, 42, lawyer, Netflix Singapore, “self-censoring information that we consider to not be socially appropriate” played a role in her trauma experience. “There’s this women’s business that we don’t talk about. It’s interesting when you look at fertility and having babies—there’s so much celebration around it in society, so much focus on the positive. But we just ignore the negative. It’s like the dirty business that no one wants to talk about”.

After a long, taxing journey trying to conceive and two pregnancies that ended in miscarriage just before the second trimester, Natalie recognised she had depressive symptoms, but kept it to herself and carried on. “It’s labelled as part of the private bucket. I compartmentalised everything and got on with it, which was really hard at the time because you have this hidden thing that you’re dealing with that no one sees. You’re showing up and no one knows that it’s all going on underneath the surface”. For Natalie, the “loss of hope” became an oppressive mental burden, “I didn’t give myself permission to talk about it. I had so many emotions that I didn’t know how to process.”

Similarly, in my case, the never ending cyclical failure of negative tests every month, a loss and countless doctors appointments full of bad news, all the while having to put on a smile took me from a place of heartbreak to the edge of breakdown. I was diagnosed by a psychiatrist with depression, but an outside observer would be none the wiser.

According to Dr Aarti Mundae, psychotherapist and director, Incontact Counselling and Training Singapore, offers a psychological perspective, “infertility does come under the trauma definition”. A lack of control and a sense of non-performance can also be damaging: “there is a lot of shame attached to not being able to conceive or just even the whole infertility piece. And this could be compounded by shame with your body—that the body is not doing what it is naturally supposed to do, that the body has failed me”. Socio-cultural factors should not be ignored when it comes to the stigma according to Dr Mundae, “I think Asian cultures in general are more taboo when it comes to talking about feelings, emotions and failures. It’s a transgenerational, cultural belief system. Infertility has a feeling and an emotion which people don’t often see. They see it as a physiological condition”.

Pregnancy blues: prenatal depression

“Is this a thing? I didn’t know it was a thing”. After suffering from postpartum depression with her first child, Michelle Holland, 43, TV presenter and Fox Sports Asia anchor was taken aback when she sensed those familiar emotions when pregnant with her second. “The feelings were very similar and I thought it can’t be, I’ve not had the baby”. Michelle was unaware of prenatal depression, “chalk this up on the list of things people don’t talk about. You’re warned that there’s postpartum depression, but nobody ever says you could have these feelings prior to giving birth”.

After seeing her obstetrician who did confirm that such a condition does indeed exist, even though she felt a sense of relief, she took no further action. Antidepressants were not entertained, “the fact is when you’re pregnant, especially when you’ve had assistance to get pregnant, you live in a bubble of fear for those nine months. You don’t want to do anything that could rock the boat—even popping a paracetamol—you question whether you need to do it”. And it was still a case of mum’s the word. “I thought I just needed to deal with it. I’ll just bite my tongue and get on with it. I never spoke to anyone about it except my doctor”. On why she thought it was her cross to bear, “I didn’t even talk to my husband about it. I rationalised it by thinking about the hormones—you’re pregnant, you’ve got chemical imbalances going on, your body is going through a lot. And what could he do about it? I didn’t think he could necessarily help me with the burden. Women are very good at gritting and bearing it”.

As Dr Kamini Rajaratnam, consultant psychiatrist, Better Life Psychological Medicine Clinic Singapore explains, “prenatal depression can masquerade as a number of different things” and it’s right from the beginning “when mum guilt starts—from the moment of conception. There are so many psycho-social issues that come up”. While most of us will experience the dreaded mum guilt at some stage, “there are some factors that predispose a mum to prenatal depression. It is usually in mums who might have had a history with depression before. A family history of postnatal depression is a very important risk factor and of course, mums who are socially isolated. A lot of us can fall into that category as we don’t have our village anymore. We don’t give birth and come home to our grandparents and mums and aunts and everyone. So these are things to look out for. But of course there are women who have never had any issues—they’re perfectly fine, then they get pregnant and it hits them”.

They say it takes a village to raise a child, but without the child and the village, those of us who do seek external help are sometimes looking in the wrong places.

The physiological and psychological impact of infertility

Unfortunately there is rarely a holistic approach to infertility. Medical physicians will typically focus on clinical treatments, drug therapy and surgery to help investigate, repair reproductive organs or synthetically compensate for any hormonal shortcomings. While often necessary and sometimes a crucial piece of the infertility puzzle, these actions can take an emotional toll and potentially even exacerbate feelings of anxiety and stress. For me, medical intervention was essential, but potentially compounded my mental health distress.

I was prescribed two different oral medications over the course of a year to help induce ovulation—Letrozole and Clomiphene. Both did not work for me, however, in addition to tufts of hair falling out, bloating that made me look pregnant and breakouts, the possible side effects of Clomid include anxiety, mood swings, sleep disturbances and more—reactions so notorious they’re known colloquially as the “Clomid Crazies”.

When it comes to pregnancy, again the onus is typically on the biological and logistical. As Michelle describes it, “when you go to baby classes, you’re taught how to put a nappy on, how to bathe your child, but you don’t learn how to deal with emotions. You are going through physical change, but there are also hormones, chemicals—it affects everything and I feel like not enough attention is put on how you are doing mentally on your journey through motherhood. When you see your gynae, you have your physical exam, but there is no push to ask how you’re doing in your head”.

Breaking the silence

When it comes to a clinical bedside manner or approach, for Dr Mundae, it could come down to a lack of psychological awareness and training, “but you are treating humans and you’re treating very tender and fragile issues of the human body—reproduction”. According to Dr Mundae, in an ideal world, alongside your fertility doctor, there wouldn’t be just a one-time counselling session, but “a designated professional who will explain and educate you on the grief, anger and despair and hope that you may experience during this event. Normalise those feelings, help you create some self-compassionate behaviours”.

From Dr Rajaratnam’s perspective, when it comes to medical doctors and prenatal depression, it’s about making mums-to-be comfortable enough to reach out, “a psychiatric assessment is beyond their scope and they also don’t have the time, but it’s about creating that safe space and awareness. Just by saying this is a tough time, a lot of other mums have had a lot of emotional upheaval and if you experience anything, please feel free to let me know and I can direct you to the resources” could potentially help.

After her ordeal, Natalie was blessed with two daughters and now leads the women’s employee resource group at Netflix Singapore called SGWomen@Netflix. The focus is on female employees and their allies and their ability to raise issues, educate and engage in meaningful conversations, especially around these sensitive subjects. “Netflix is a company that is about storytelling, and I do believe there is a lot of power in storytelling and people sharing”. But she has found most women still want to keep their journeys anonymous, “even that says a lot about stigma in society, but I do find a lot of people are happy when they’ve finally talked about it, because it’s releasing that burden”.

“I wish when I started feeling those familiar feelings come back that I would’ve said something immediately”. From Michelle’s viewpoint, open dialogue with healthcare professionals from the outset would be the first step to healing. “It probably took me my third visit of feeling those emotions to actually blurt it out and ask my doctor is this normal? Because I was having an inward battle with myself. I wish that it was a question that was asked. “How are you coping?” never gets asked. Perhaps if you’re newly pregnant, your doctor lays it out for you and says “potentially you could be feeling these emotions and if you do, let me know”. That’s all it takes. Just knowing someone has your back and if you did have those feelings, you would have an open channel to talk about it.”

If you are experiencing the infertility and prenatal-related depression, you are not alone. Contact KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital Women’s Mental Health Service division or support: pnd@kkh.com.sg.

Submit a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Blogs

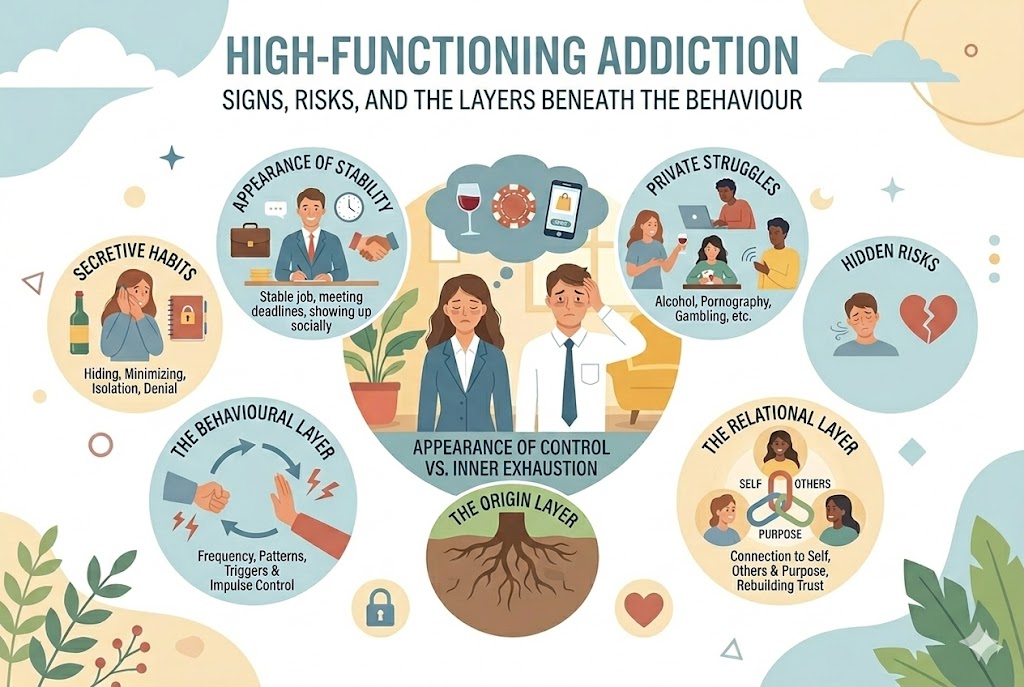

High-Functioning Addiction: Signs, Risks, and the Layers Beneath the Behaviour

5 March, 2026

Addiction isn’t always visible. Some individuals continue to work, parent, meet deadlines, and show up socially – all while privately struggling wi...

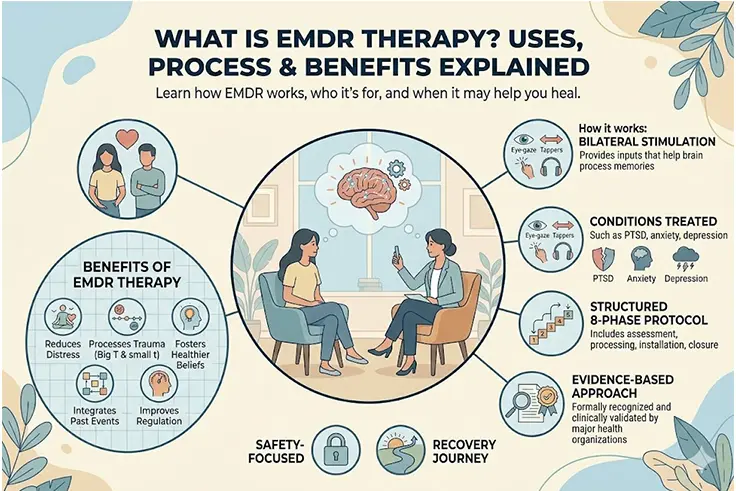

What Is EMDR Therapy? Uses, Treatment & Benefits Explained

2 March, 2026

What is EMDR therapy? EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing) therapy is an evidence-based approach that helps individuals process and heal fr...

What to Do When Your Partner Refuses Couples Therapy

6 February, 2026

When a partner refuses couples therapy or a partner doesn’t believe in therapy, it can leave you feeling stuck, alone, and carrying the emotional weight ...